As one of the world’s largest displacement crises, there remain over 23.7 million people in Afghanistan who are in need of humanitarian aid and protection assistance. Decades of conflict, natural disasters, and poverty amalgamate with the onslaught of Taliban rule, leaving the future life of families in Afghanistan unpredictable and unstable. The Taliban’s return to power in Afghanistan has resulted in one of the largest displacements in the country’s history. With nearly 5.8 million refugees internationally and 10.8 million displaced internally, the crisis in Afghanistan continues to mount. This instability, along with constant human rights violations by the Taliban, leaves over 40 million people (more than half the country’s population of women and children) at risk of food insecurity and poverty.

Refugees are Forced to Return to Afghanistan

Over the past two years, two of Afghanistan’s neighbours, Iran and Pakistan, have hosted substantial numbers of Afghanistani refugees and migrants fleeing conflict and the Taliban’s return to power in 2021 and earlier. Both countries have increasingly compelled these refugees to return to Afghanistan. In 2025 alone, more than 2.1 million Afghans were forcibly returned or pressured into returning, including over 1.5 million from Iran and approximately 352,000 from Pakistan.

The influx of returnees, both voluntary and forced, has placed significant strain on an economy that remains fragile, underdeveloped, and unable to absorb mass population movements. Many Afghanistani refugees face deportation, legal uncertainty, and lack of documentation in host countries, leading them to return despite the ongoing risks of poverty, repression, and instability. This large-scale return, for which neither the Taliban authorities nor the humanitarian sector were adequately prepared, has brought well over one million additional people back into the country—many of whom have never lived an established life in Afghanistan.

Compounding the humanitarian challenges, the Taliban and Kuchi groups have reportedly forced residents to abandon their homes and lands across several regions, including Bamyan, Daikundi, Maidan Wardak, Kabul, Ghazni, Badakhshan, and northern provinces. These evictions have further destabilised already vulnerable communities and intensified hardships for women and children, who face heightened exposure to poverty, displacement, and gender-based violence.

Under these conditions, some families—lacking income, support structures, or protection mechanisms—have resorted to negative coping strategies. In certain cases, this has included the forced marriage of young girls in exchange for financial compensation to cover basic household expenses.

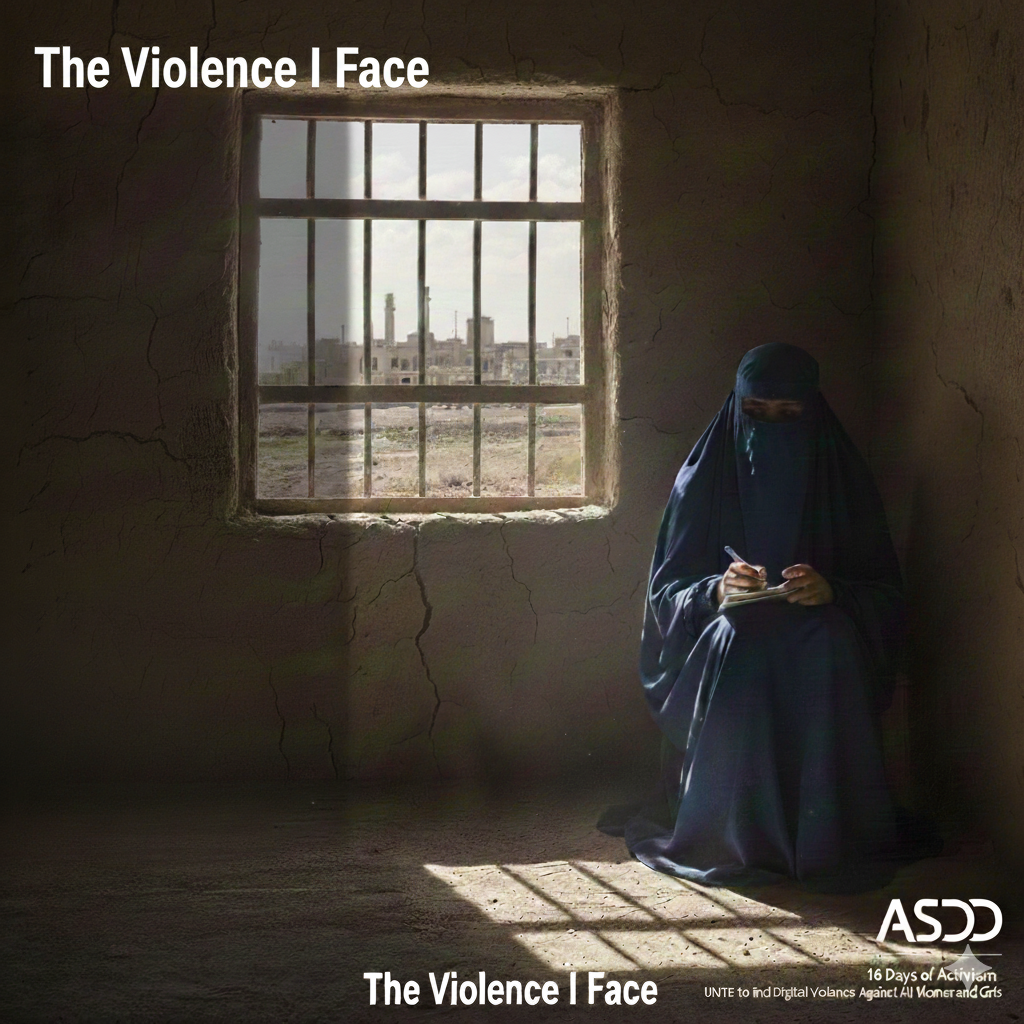

Women and girls remain disproportionately affected by these converging crises. Living under a regime that imposes systemic discrimination and severe restrictions on their rights, their forced return and subsequent displacement place them at even greater risk, deepening an already severe humanitarian and protection emergency.

Natural Disasters Contribute to Instability

Afghanistan has faced several severe natural disasters over the past year, deepening instability and intensifying humanitarian needs. In February 2024, a massive landslide in Nuristan Province destroyed an entire village, killing at least 25 people and demolishing around 20 homes. On 31 August 2025, a magnitude-6.0 earthquake struck Kunar, Nangarhar, and Laghman provinces, flattening villages, killing more than 2,200 people, and rendering over 6,700 homes uninhabitable. Only a few months later, in early November 2025, a magnitude-6.3 earthquake hit northern Afghanistan near Mazar-i-Sharif, killing at least 20 people and damaging hundreds of homes as well as cultural sites such as the historic Blue Mosque. These repeated disasters have displaced tens of thousands of families, strained an already fragile infrastructure, and pushed vulnerable communities further into poverty. Women and children remain disproportionately harmed by these crises, facing heightened risks of homelessness, insecurity, and exploitation as a result.

Among all these humanitarian crises, the institutionalised and systematic laws and edicts imposed by the Taliban have placed women under even greater life-threatening conditions. Medical regulations prohibiting male doctors from treating women have resulted in many injured women being left without care following earthquakes and other emergencies. Because women are no longer permitted to study medicine or become health professionals, countless women lack local access to essential medical treatment and endure prolonged physical suffering. Furthermore, Taliban mandates requiring women to be accompanied by a male guardian when leaving the home mean that widows and women-headed households cannot travel to clinics or reach external support services. In addition, the Taliban’s ban on women working with humanitarian organisations, including the United Nations and international NGOs, has further restricted the provision of support to women in these crises. Female staff are essential for accessing and assisting women in conservative communities. As a result, many women remain without medical care or humanitarian assistance for months—or indefinitely, compounding the severity of Afghanistan’s already acute humanitarian emergency.

The Economic Impact of Women’s Repression

The dysfunction of the Taliban’s de facto government has severely undermined Afghanistan’s development and infrastructure, offering little relief to the country’s deepening poverty. Afghanistani women bear a disproportionate share of this burden, as their only legal means of income is through male family members, leaving them economically dependent and socially vulnerable.

Since the Taliban regained power in 2021, Afghanistan’s GDP has contracted sharply. The systematic exclusion of women from economic participation is directly responsible for a significant portion of the estimated 29% overall decrease, according to the UNDP. Restrictions on women’s education and employment limit individual livelihoods and weaken the broader economy. According to UN Women, banning women from working and studying has cost Afghanistan approximately 2.5% of its GDP annually. This economic loss compounds household poverty, reduces access to essential services, and exacerbates women’s vulnerability to exploitation and social marginalisation.

Beyond direct financial consequences, the repression of women undermines human capital, innovation, and productivity across sectors. Women, who constitute roughly half of Afghanistan’s population, are prevented from contributing to healthcare, education, governance, and business—areas that are critical for national recovery. The economic marginalisation of women therefore creates a vicious cycle: families remain impoverished, communities lack skilled labour, and the country’s long-term development prospects continue to deteriorate.

The overlapping crises in Afghanistan—forced returns of refugees, internal displacement, natural disasters, and the systematic repression of women—have created an environment where women and girls are disproportionately vulnerable to violence, exploitation, and deprivation. As the 16 Days of Activism Against Gender-Based Violence highlight, these global campaigns are not only a call to end physical and sexual violence but also to address structural and systemic forms of oppression that perpetuate harm. In Afghanistan, Taliban policies restricting women’s education, work, and access to healthcare, combined with economic marginalisation and displacement, represent institutionalised violence that undermines women’s safety, autonomy, and survival. Recognising these compounded threats during the 16 Days of Activism underscores the urgent need for international attention, humanitarian support, and policy interventions to protect Afghanistani women and girls, ensuring their rights, dignity, and security are no longer disregarded.